Warum ziehen die USA Europa wirtschaftlich davon?

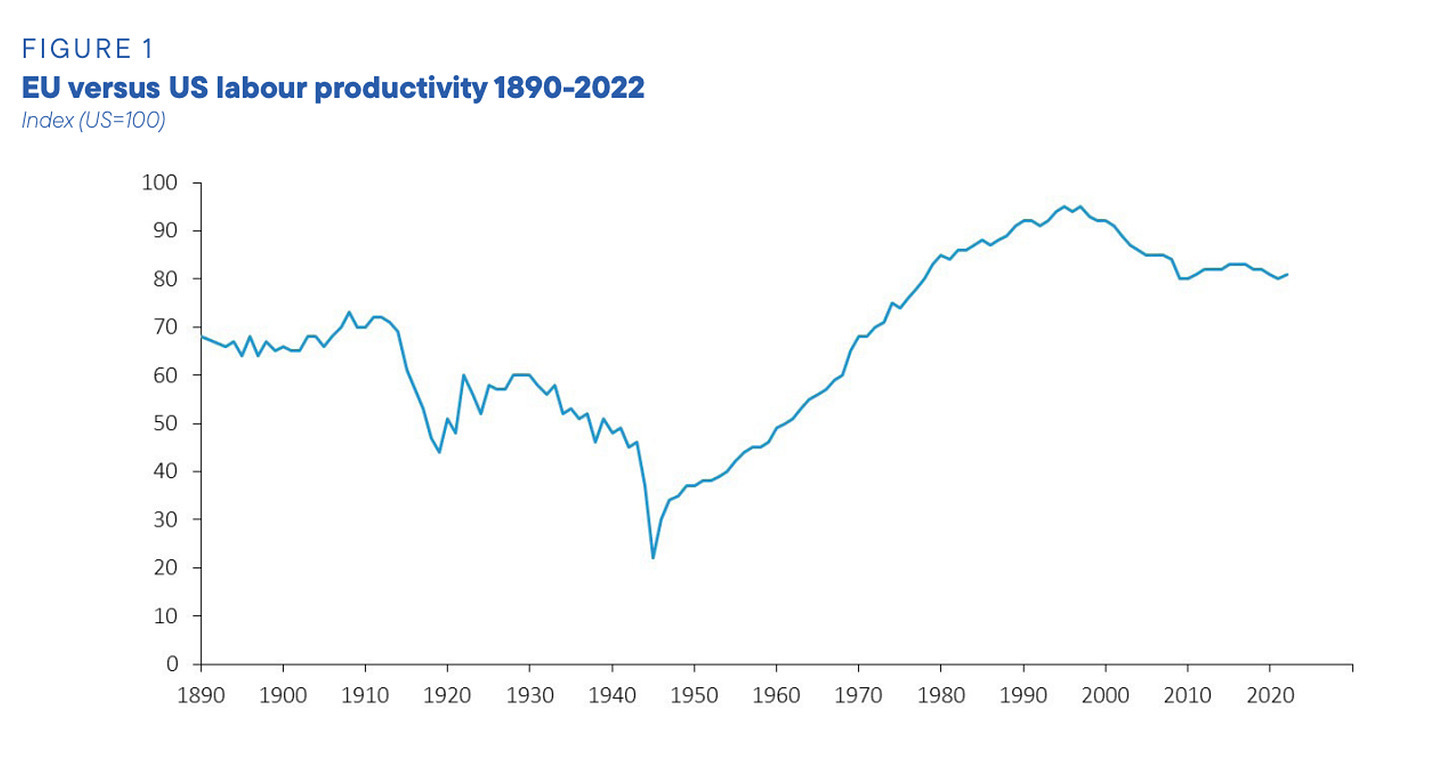

Es gibt unter Ökonom:innen, wirtschaftspolitischen Beobachter:innen und in der EU-Bürokratie derzeit eine Debatte darüber, warum die USA Europa beim BIP pro Kopf und bei der Produktivität, also bspw. dem BIP pro Arbeitsstunde, davon ziehen.

Die FT fasst zusammen:

US labour productivity has grown by 30 per cent since the 2008-09 financial crisis, more than three times the pace in the Eurozone and the UK. That productivity gap, visible for a decade, is reshaping the hierarchy of the global economy. Economic growth in the Eurozone has been a third of the US’s since the pandemic, and output is set to expand by just 0.8 per cent this year, according to the IMF.

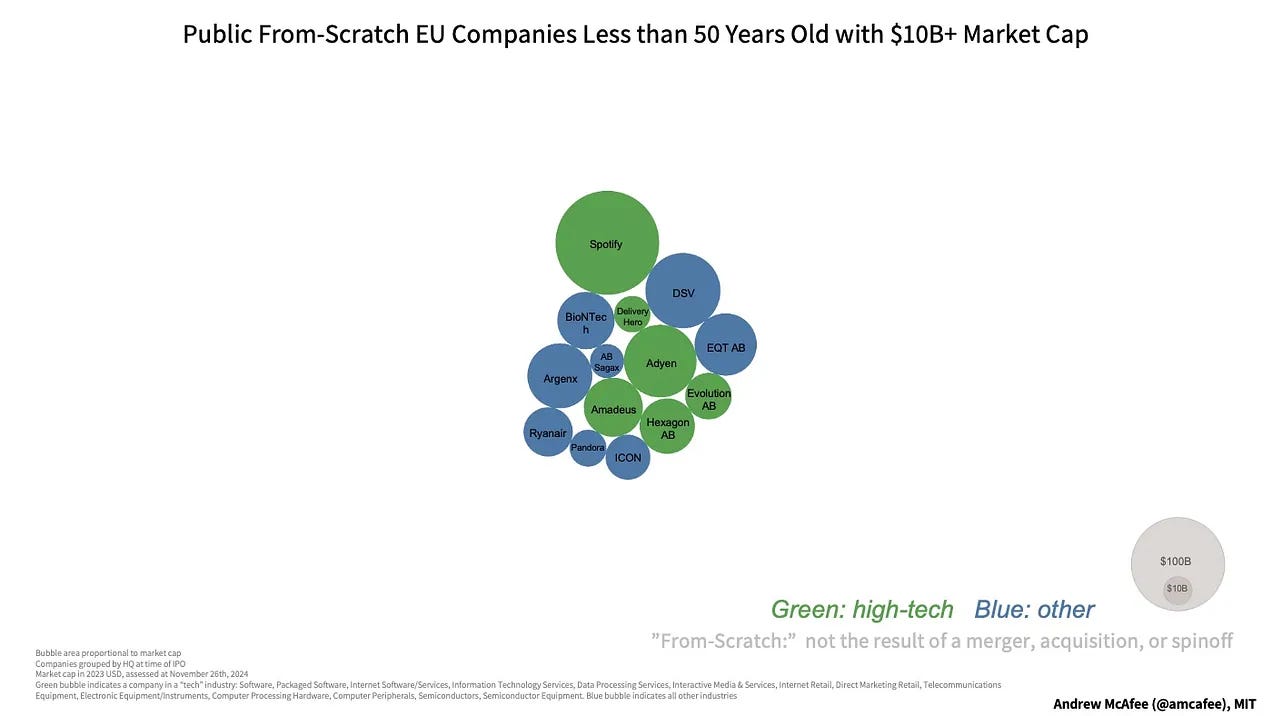

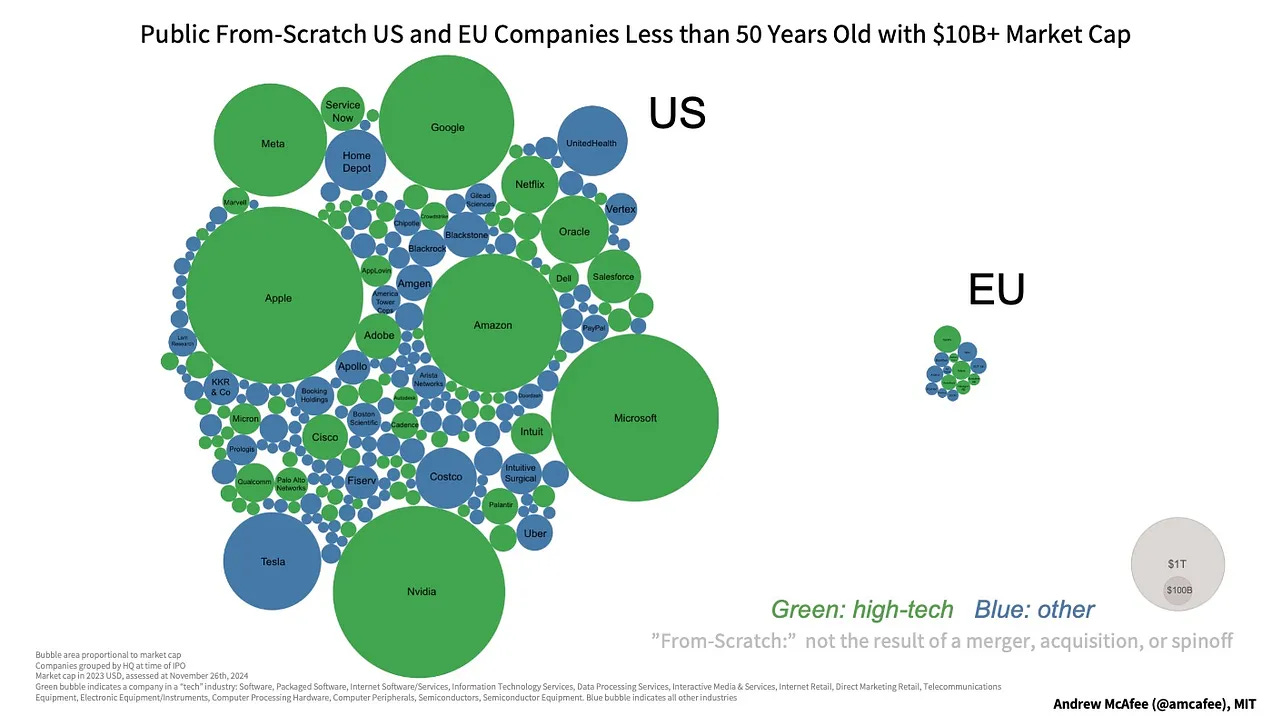

Andrew McAfee, Betriebswirt am MIT, zeigt in seinem Newsletter, wie viele EU-Firmen in den vergangenen 50 Jahren entstanden sind, die heute über zehn Milliarden Euro Marktwert haben.

Grüne Bälle zeigen High-Tech-Firmen, blaue alle anderen:

Das sieht schon mal nach sehr wenig aus, wenn man die USA daneben stellt, sieht es noch nach viel, viel weniger aus.

Der Ökonom Scott Sumner relativiert in seinem Newsletter die Debatte zuerst:

My own view is that some of this is overstated. When I travel to places like Europe, Japan, Canada and Australia, I see lots of things they do better than the US. Indeed even China (with a per capita GDP on par with Mexico) is vastly superior to the US in things like subways, high-speed rail, safe streets. Overall, I still greatly prefer conditions in the US to China, but there is more to life than GDP/person.

Danach stimmt er aber trotzdem in den Chor des Abgesangs auf Europa ein und macht aufgeblähte Staatsausgaben und staatliche Umverteilung verantwortlich, genau wie Überregulierung und auch schlechteren Zugang zu Kapital.

Da ist zum Teil sicher etwas dran, aber Paul Krugman hat in seinem Newsletter die meiner Meinung nach spannendste Einordnung zum Thema.

Almost everything I read focuses on things like excessive regulation in Europe, a financial culture that is willing to take risks and so on. I’m not saying that none of this is relevant. But one way to think about technology in a global economy is that development of any particular technology tends to concentrate in a handful of geographical clusters, which have to be somewhere — and when it comes to digital technology these clusters, largely for historical reasons, are in the United States. To oversimplify, maybe we’re not really talking about American tech dominance; we’re talking about Silicon Valley dominance.

Das ist genau das, was wir im FT-Zitat zu Beginn gelesen haben: Die USA ziehen Europa bei der Arbeitsproduktivität davon. Wenn man nun aber den Unterschied zwischen den US- und EU-Firmen vergleicht, zeigt sich, so Krugman, dass de facto einzig und allein der Tech-Sektor mit bspw. Google und Meta verantwortlich ist.

Krugman zitiert aus dem Draghi Report:

Excluding the main ICT sectors (the manufacturing of computers and electronics and information and communication activities) from the analysis, EU productivity has been broadly at par with the US in the period 2000-2019.

The remaining disadvantage in productivity growth versus the US is significantly reduced to 0.2 percentage points (0.8% productivity growth for the US versus 0.6% for the EU).

The actual EU-US gap can be considered close to zero as EU 27 productivity growth is 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points higher than the EU10 selection (for which EU KLEMS data is available).

For 2013-2019 the role of ICT is even more striking, as the EU productivity growth excluding the main ICT sectors exceeded that of the US by some margin.

Krugman schreibt weiter:

So it’s all tech, although the report concedes that “the US also has high productivity growth in professional services and finance and insurance, reflecting strong ICT technology diffusion effects.”

Which brings me to my point: both tech and finance are highly concentrated geographically.

Warum konzentrieren sich Industrien oft lokal? Krugman zitiert Alfred Marshall:

if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas.

Manchmal reicht auch eine Person:

Seattle is what it is because Bill Gates grew up there. Stanford University played an important role in Silicon Valley’s rise, but it’s unclear whether it would have become what it is if two guys named Hewlett and Packard hadn’t started a business in a garage.

What I’m suggesting is that America’s tech advantage may bear considerable resemblance to Britain’s banking advantage. That is, it may have less to do with institutions, culture and policy than the fact that for historical reasons the world’s major technology hubs happen to be in the United States, and remain there for the usual Marshallian reasons.

London sei ein Finance Hub, weil Großbritannien einmal ein Weltreich war und das den Grundstein für Finanzgeschäfte legte. Sind einmal schlaue Leute in Finance an einem Ort, ziehen sie andere an und so weiter. Gerade, wenn man von einem Standort aus die ganze Welt versorgen kann, wie in der Tech-Industrie, ist der Effekt stark.

Auch die besseren Finanzmärkte in den USA sind laut Krugman großteils auf Silicon Valley zurückzuführen. Denn dort würde hauptsächlich investiert werden.

Hier alle Beiträge zum Nachlesen.

Andrew McAfee:

Scott Sumner:

Paul Krugman: