Eine neue Ära der Deregulierung?

Der Economist hat in der aktuellen Ausgabe eine hochinteressante Aufarbeitung der globalen Deregulierungswelle, die durch viele Länder zieht.

Das unsympathische Gesicht der Deregulierung ist Elon Musk, aber es gibt, wie das Magazin differenziert beschreibt, tatsächlich viel Luft für weniger Bürokratie.

He brandished a chainsaw at campaign rallies, to signify his eagerness to clear-cut the thickets of bureaucracy and regulation impeding the economy’s progress. Perhaps more strikingly, he has actually lived up to this act. In November Javier Milei, the president of Argentina, told The Economist he had already taken 800 steps to reduce red tape and planned 3,200 more such “structural reforms”.

He is not alone. Politicians around the world, on both the right and the left, are embracing deregulation. Donald Trump has created a “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) headed by Elon Musk, an entrepreneur, to shrink government and slash red tape. He has also initiated a maelstrom in the civil service. Last year New Zealand set up a “ministry for regulation”, to which citizens can report any “red-tape issue”. On January 29th the European Commission pledged to cut corporate reporting requirements by 25%, and by 35% for small firms.

Even countries renowned for their powerful states are joining in. François Bayrou, France’s prime minister, promises “a strong movement of de-bureaucratisation”. Vietnam plans to abolish a quarter of government agencies. India’s bureaucracy, a byword for Dickensian obstruction, is slimming down. The push to reform how Western governments operate “is potentially bigger than the Reagan-Thatcher revolution” of the 1980s, argues John Cochrane of Stanford University.

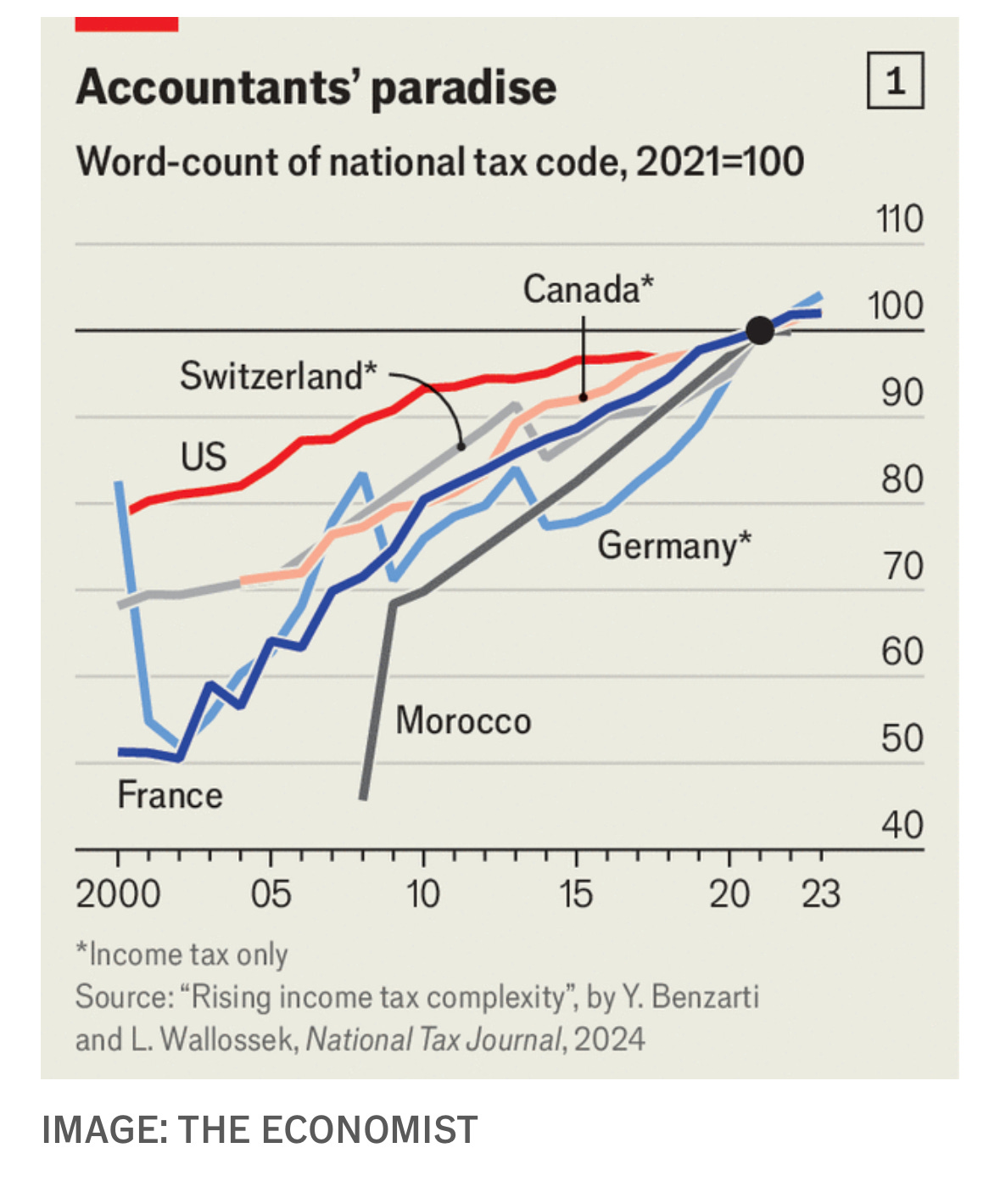

The world is not short of red tape to cut. According to the Regulatory Studies Centre at George Washington University, federal regulations in America now exceed 180,000 pages, up from 20,000 in the early 1960s. Official figures suggest that the federal government imposes 12bn hours of paperwork on Americans each year, or about 35 hours per person, up from 27 hours per person in 2001. The complete text of all German laws has 60% more words than in the mid-1990s. Over the past 20 years tax codes from Canada to Morocco have swollen (see chart 1).

It seems logical that as a society evolves, some new rules should be added and some old ones scrapped. Yet research by Davide Furceri of the IMF and colleagues finds “a remarkable slowdown” in rescissions (Anm.: Aufhebung) since the 1990s in rich and poor countries alike. The share of Americans who think the government does “too much” currently exceeds those who want it to “do more” by an unusually wide margin, according to Gallup, a pollster.

Productivity statistics offer another clue. Data from Britain suggest that the administrators of government benefits are 20% less productive than they were in the late 1990s. Excluding defence, Canada’s federal bureaucracy is no more productive than it was a decade ago, even as private-sector productivity has grown by 7%. In Australia productivity in non-profit professions, including public administration, fell over the past decade. According to a recent study from the European Central Bank which focused on the euro area’s five biggest economies, “the public sector made a negative contribution to productivity per person” over the past five years.

Many rules are clearly pointless. Hundreds of thousands of firms in California must put up signs stating that their premises “contain chemicals known to the state of California to cause cancer”. Other firms must post signs in bathrooms telling staff to wash their hands. Hotels must have signs next to pools urging people with “active diarrhoea” not to bathe. In France a house cannot be sold unless a notary reads the contract aloud in the presence of the buyer and seller. Each of these bureaucratic follies is typically only a minor expense and inconvenience. Cumulatively, however, they stifle economic activity, like Gulliver tied down by lots of pieces of string.

Economists have tried to calculate the macroeconomic costs of all these bits of string. Mr Bayrou has cited a paper by Bruno Pellegrino of Columbia University and Geoffery Zheng of New York University, which finds that red tape costs the French economy close to 4% of GDP every year. (“Insupportable!” declares the prime minister.) The OECD estimates that compliance costs eat up around 4% of business output in member-countries on average. Chang-Tai Hsieh of the University of Chicago and Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley, attribute similarly staggering costs to land-use regulations.