Die ärmsten Länder der Welt wachsen wieder langsamer als die reichsten

Since the Industrial Revolution, rich countries have mostly grown faster than poor ones. The two decades after around 1995 were an astonishing exception.

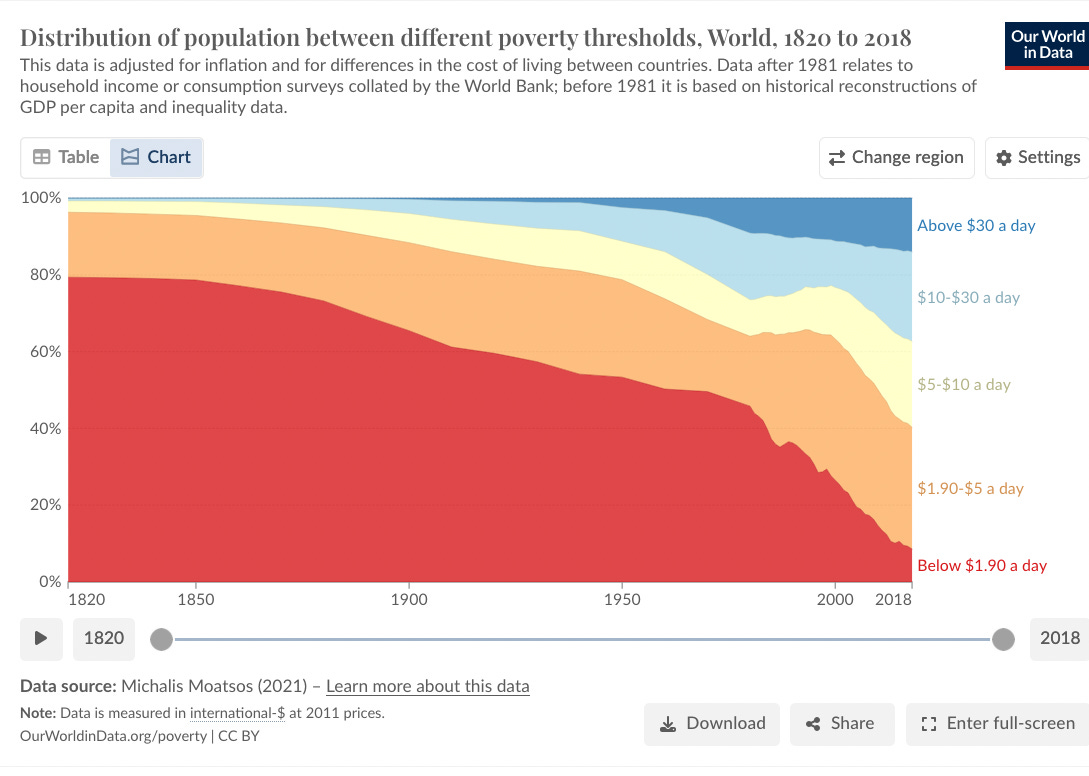

During this period gaps in GDP narrowed, extreme poverty plummeted and global public health and education improved vastly, with a big fall in malaria deaths and infant mortality and a rise in school enrolment.

Globalisation’s critics will tell you that capitalism’s excesses and the global financial crisis should define this era. They are wrong. It was defined by its miracles.

Today, however, those miracles are a faint memory. As we report this week, extreme poverty has barely fallen since 2015.

Measures of global public health improved only slowly in the late 2010s, and then went into decline after the pandemic.

Malaria has killed more than 600,000 people a year in the 2020s, reverting to the level of 2012.

And since the mid-2010s there has been no more catch-up economic growth.

Depending on where you draw the line between rich and poor countries, the worst-off have stopped growing faster than richer ones, or are even falling further behind.

For the more than 700m people who are still in extreme poverty—and the 3bn who are merely poor—this is grim news.

Hier die aktuellsten Daten der Weltbank, die diese Entwicklung zeigen:

Hier die Entwicklung der Armut auf der Welt in den vergangenen 200 Jahren via Our World In Data. In rot ist die extreme Armut, die massiv zurückgegangen ist – jetzt aber eben nur mehr langsam sinkt. Es gibt noch jede Menge zu tun.